Antifa in East Germany and its origin in the GDR

Christin Jänicke

More than 30 years after the end of the GDR, there is still an East-West divide in society, which is also reflected in the current antifa movements in Germany. In recent years, the view of the East has once again become more closely associated with and shaped by the far right. It is overlooking the fact that there is antifascist activism countering the far right, which has its origin in the GDR.

In 1987, no one in East Berlin would have expected a rock concert in a church to become the birth of the independent Antifa. But the Nazi attack on October 17, 1987, on the Zion Church, triggered a unique self-organization within the GDR. It was not the first, and indeed not the last, act of far-right violence in the GRD; already at the beginning of the 1980s first signs of neo-Nazi groups and racist attacks became known. However, the attack from 30 neo-Nazis on around 400 remaining guests, while the police stood by and did not intervene, was different. While the Nazi activities had previously been played down and concealed, the attack and the subsequent political pressure led to a clear about-turn by the GDR authorities. Within the left-wing scene, it gave rise to discussions about self-defence. Calls for increased public awareness of neo-Nazis and racism grew louder.

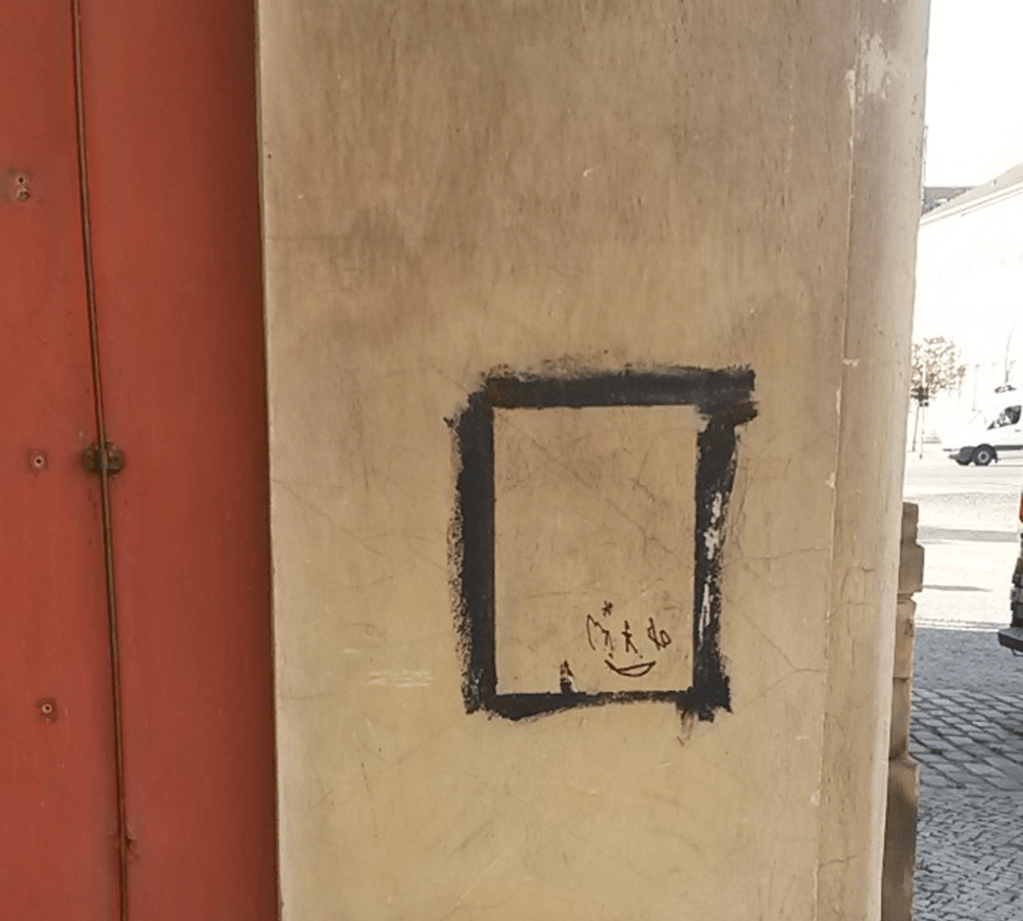

In response, activists in various cities across the GDR including Berlin, Dessau, Dresden, Guben, Halle, Potsdam, and Rostock established their own groups. Antifa Potsdam, the first independently organized Antifa group, was formed shortly after the attack on the Zion Church. Their first known action took place on the night of 5 to 6 November 1987. They posted flyers and graffiti with the message “Warning: Neo-Nazis in the GDR too” on the walls all over Potsdam. Today, more than 30 years later, a black frame on the back of the Potsdam Film Museum serves as a reminder of the early days of an independent Antifa movement that emerged in the GDR.

A black frame at the Potsdam Film Museum commemorates the first Antifa action in the GDR. Source: Ch. Jänicke

The state and social upheaval of 1989/90 was a milestone for today’s Antifa movement. However, under the assumption of a common history of resistance, little attention has been paid in previous retrospectives to the fact that an independent movement emerged in East Germany, which began in the late GDR and developed its own profile.

See the following literature for further information:

Jänicke, Christin. ‘The Invisible “Antifa-Ost”. The Struggles of Anti-Hegemonic Engagement in East Germany’. PaCo, no. Special Issue ‘Antifa from Below’ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1285/I20356609V17I1P64.

Weiß, Peter Ulrich. ‘Civil Society from the Underground: The Alternative Antifa Network in the GDR’. Journal of Urban History 41, no. 4 (2015): 647–64.

For German speakers, this archive contains original documents from activists, as well as photographs and other related materials: www.antifa-nazis-ddr.de

Antifa in West Germany and the old FRG

Scene from the 1932 Antifaschistische Aktion conference.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Nils Schuhmacher

The history of German anti-fascism is rooted in a defeat. It was neither able to prevent the Nazis from seizing power, nor did it contribute decisively to its end. This painful historical experience forms the background to the founding of the two German states and also the various antifascist protest movements that have emerged in (West-)Germany since the 1950s. The spectrum of these actors is broad. Organisationally, it ranges from members of parties, trade unions and churches to grassroots groups, politically from liberal-democratic to radical, state critical groups. Despite the diversity of these circles and their often great distance from each other in everyday life, the various actors are similar in their humanistic and moral stance and in their claim to oppose fascism, already in its preliminary forms. At the same time, the means and ‘long-term goals’ were and are very different. In particular, the forms of militant and confrontational antifascism and the political scope attributed to the fight against fascism constantly lead to political criticism from third parties and to ‘internal’ division.

Anti-fascist protests have accompanied the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. They were triggered, for example, by debates on how to deal with Nazi criminals in the 1950s, the emergence of a parliamentary far right in the 1970s, by militant neo-Nazism in the 1980s and by the mass right-wing violence of the 1990s. The composition of the protest groups varied greatly in each of these scenarios.

The emergence of radical antifascism in the late 1970s marked a significant turning point in the history of West German antifascism. This gave rise in the 1980s to the spectrum of autonomous groups that have since operated under the name ‘Antifa’.

Source: https://anarchiststudies.org/commitment-and-continuity/

The 1990s were the height of this grassroots antifascist movement. It developed far away from organisations and parties, initially operating mainly in the public sphere. The particular strength of this self-organised anti-fascism stemmed from its roots in various youth cultures and its ability to hinder the public appearance of the far right. In this sense, it was significantly responsible for preventing the consolidation of fascist groups and for organising solidarity with victims of the fascist threat. And it has effectively acted as a social early warning system and thematic agenda-setter.

With the new millennium, this movement lost momentum, not least due to the institutionalisation of the fight ‘against the right’ in Germany through the initiation of State subsidised programmes. Nevertheless, self-organised antifascism remained a key factor into the second decade––in the context of mobilisations, as well as in research, public information and education.

The last few years have been characterised by a clear loss of significance of ‘classic’ autonomous antifascism as a political actor. At the same time, new organisations and forms of practice are emerging in the confrontation with new right-wing movements and parties––sometimes under the cipher of ‘antifascism’, sometimes also as a commitment ‘against the right’.

Source: https://www.omas-gegen-rechts.org.

See the following literature for further information:

Schuhmacher, Nils (2013): Sich wehren, etwas machen. Antifa-Gruppen und -Szenen als Einstiegs- und Lernfeld im Prozess der Politisierung. In: Schultens, René/Glaser, Michaela (eds.): ‚Linke’ Militanz im Jugendalter. Befunde zu einem umstrittenen Phänomen. Halle/S.: Deutsches Jugendinstitut, 47-70.

Schuhmacher, Nils (2014): „Nicht nichts machen”? Selbstdarstellungen politischen Handelns in der Autonomen Antifa. Duisburg: Salon Alter Hammer.

Schuhmacher, Nils (2015): Die Antifa im Umbruch Neuformierungen und aktuelle Diskurse über Konzepte politischer Intervention. In: Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 28(2), 5-16.

Schuhmacher, Nils (2017): „Küsst die Faschisten“. Autonomer Antifaschismus als Begriff und Programm. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte. 42-43, 35-41.